Eye diseases

Ocular tumours

What are ocular tumours?

Ocular tumours can affect any tissue in the eye. Whether or not they are benign –which is confirmed by a biopsy–, all ocular tumours must be assessed and monitored by specialist ophthalmologists to ensure the well-being of the eye, the eyesight and, ultimately, the life of the patient is not jeopardised.

Depending on whether they originated in the eye or were the result of metastasis from cancer in another part of the body, we differentiate between primary ocular tumours and secondary ocular tumours. In women, secondary ocular tumours are often associated to breast cancer. In men, metastatic ocular tumours are often from lung cancer.

Types of ocular tumour

- Eyelid tumours: these account for half of all tumours seen by ophthalmologists and often costs of masses, nodules or bumps on the eyelids, although some are flat. They are generally benign, but must be monitored because some are not, and the malignant tumours include the most common basal-cell carcinoma.

- Orbital tumours: these are located anywhere in the eye socket (cavity in which the eyeball is housed). They are mostly benign, but they must be controlled in case they increase in size.

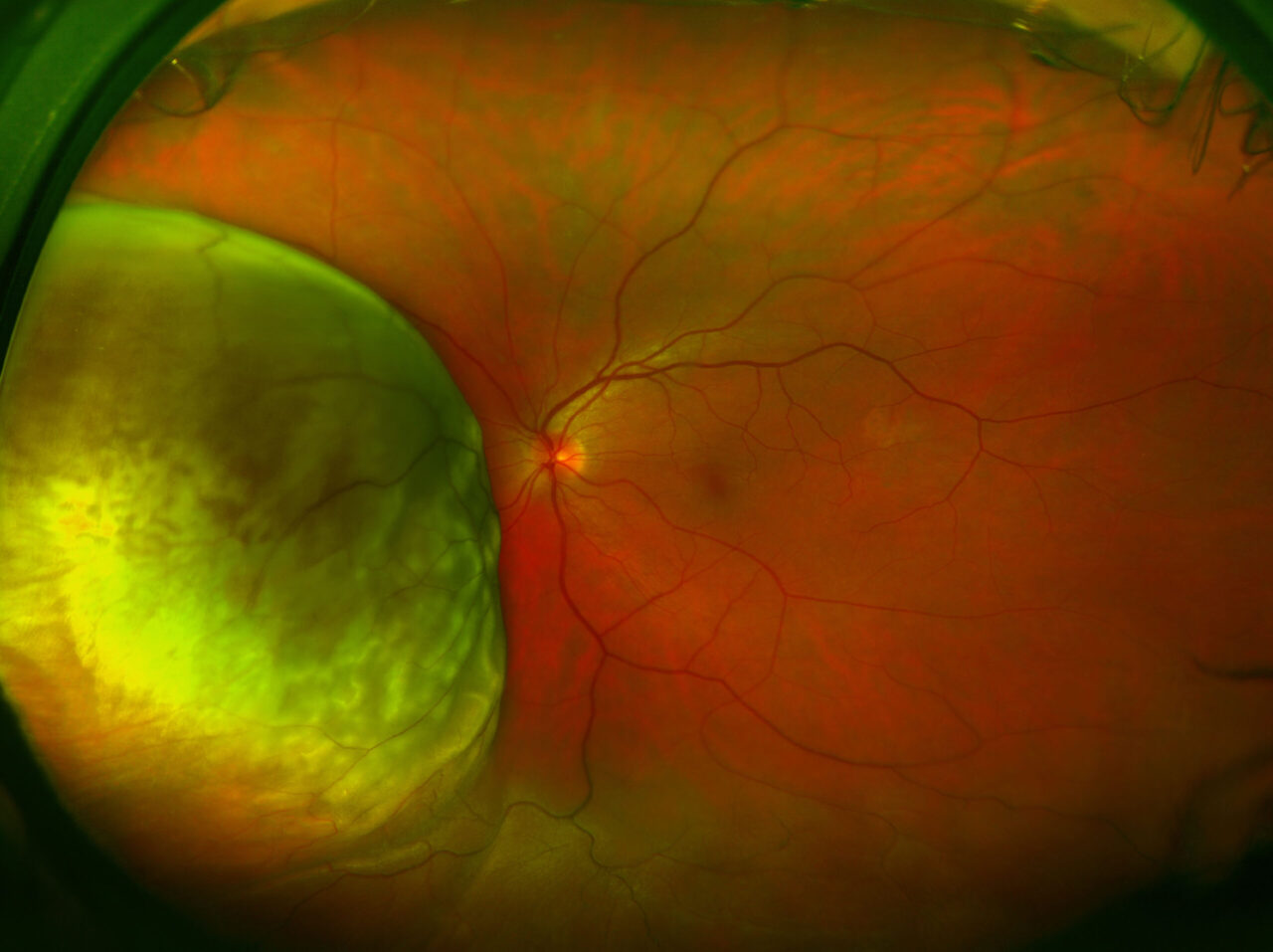

- Intraocular tumours: these affect the internal structures of the eye, and include the most frequent primary malignant tumour in adults, choroidal melanoma. This should not be confused with choroidal hemangioma, which also affects the same tissue (the layer between the retina and the sclera at the rear of the eye) but which is benign. Furthermore, in the case of children, the most frequent primary malignant tumour is the retinoblastoma, which occurs in the retina and can occasionally also appear in adults.

There are also tumours that affect other structures, such as the conjunctiva, the iris, the tear duct or the optic nerve.

Symptoms

Causes and risk factors

Treatment

The symptoms are very varied, depending on the location of the tumour. Those affecting the eyelids are most evident, as they often involve noticeable changes to the surface of the eyelid. However, they are often disregarded because they can initially be confused, for example, with a stye. Eyelid tumours might grow very slowly and are not often painful. Some signs of suspected malignancy are: ulceration, bleeding, irregular edges and loss of eyelashes.

Orbital tumours are often only noticed when they grow too large and, because of their size, lead to “bulging eyes” or exophthalmos, eyelid retraction (so that the eye is open too widely), strabismus and double vision, and even vision loss due to a compressed optic nerve.

This vision loss, and the appearance of retinal detachment or a haemorrhage inside the eye, might also alert of the existence of intraocular tumours that are otherwise silent and go unnoticed. This unexpected vision damage might also alert of tumours in other parts of the body, such as patients with lung cancer and ocular metastasis, which is discovered following a visit to the ophthalmologist.